From The Hibernian Cannibal – who consumed a live cockerel whole and then downed it with a pint of brandy – topping the bill in May 1699, to Matthew Bourne’s celebrated ballet, Sleeping Beauty, on stage last winter: Sadler’s Wells has lived many lives.

We take a look at London’s second oldest theatre since the Restoration of the English monarchy, following its long-drawn identity crisis before it finally transformed into an iconic dance house.

Sadler’s Wells has been home to a huge range of City Academy’s creative and performing arts classes over the last 8 years, so we thought it was high time to pay tribute to the rich and intriguing history of one of our premier venues.

1600s – 1900s

Sadler’s Wells is a spring of inspiration, literally.

Before it became known as the artistic venue it is today, it was a ‘Musick House’ in the small manor of Isledon (now the borough of Islington), built by Richard Sadler who was a Surveyor of Highways as well. In 1683, he ordered the gardens be dug up for road construction and there he discovered a monastic spring. Calling upon his storytelling abilities, he claimed the water could remedy “dropsy, jaundice, scurvy, green sickness and other distempers to which females are liable”.

The well’s supposed medicinal qualities, endorsed by Sadler’s friend and fellow of the College of Physicians, Dr. Morton, brought the property to national attention, with 500-600 of the most aristocratic and fashionable folk flocking in.

At the turn of the next century, Sadler decided to rival Tunbridge and Epsom wells and put on ballad singers alongside circus acts like juggling, tumbling, rope dancing and wrestling, as well as the obligatory dancing dogs and singing duck.

However, what was then rural London, suddenly experienced an outbreak of wells, and the exclusivity of Sadler’s Wells’ “sweet gardens and arbours of pleasure” declined, as did the calibre of the clientele and quality of entertainment.

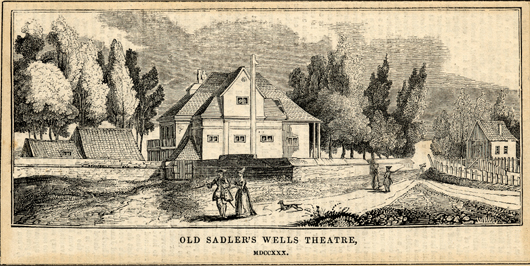

Illustration of the theatre, dated 1730, from the Islington Local History Centre archive

By the mid-18th century, Sadler’s Wells’ management decided to do something about its image and attempted to fill the gap left by the two respected Theatres Royal in the centre of the city – Covent Garden and Drury Lane – both of which confined operations to autumn and winter. Summer was for the taking. In 1765, the man on the job was Thomas Rosoman, who had the theatre rebuilt so that it could air opera productions to rival the stage dramas of the West End, erecting a new stone facade in just seven weeks and for the sum of £4225, about £701,350 in today’s money.

For all of Rosomon’s good intentions, the beer brewed from the spring waters still hogged the limelight, and ultimately stole the show. Despite celebrated thespian, Edmund Kean, and the great clown and comedian, Joseph Grimaldi, gracing its stage, by 1801 the theatre was better known for its spectacles – from scenes of sea battles (naval dramas devised to boost national morale), to entirely accidental stampedes resulting in the deaths of 18 people. “The theatre was in the condition of being entirely delivered over to as ruffianly an audience as London could shake together…Fights took place anywhere, at every period of the performance”, said Charles Dickens sometime in the 1830s – a period characterised by public drunkenness and uncivilised behaviour that meant patrons had to be escorted after dark.

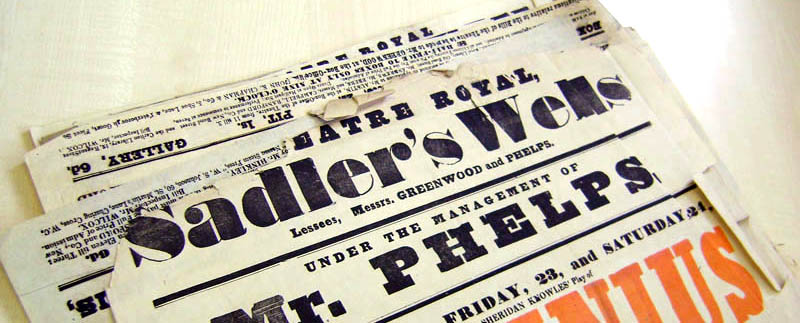

A newspaper headline on Sadler’s Wells’ newly appointed manager, Samuel Phelps – from the Islington Local History Centre collection

Following that, Sadler’s Wells enjoyed a brief stint of Shakespeare. Thanks to the passing of a parliamentary act, the then actor-manager, Samuel Phelps, was able to break the duopoly of the Theatres Royal and present a famous run in 1843. But it didn’t last long. A mere 20 or so years later, the theatre suffered the indignity of being converted, at various points, into a roller-skating rink, a prize fight arena and then a cinema. Wounded after centuries of criticism and declared a dangerous structure; it finally closed its doors in 1915.

1900s – today

Lillian Baylis – portrait from the Sadler’s Wells collection at Islington Local History Centre

That could easily have been the end, but it transpired to be a turning point. Angel Station had opened at the beginning of the century, creating a direct gateway into Islington for the public, and by the late 1920s, Lillian Baylis became the most significant person in the modern history of Sadler’s Wells. She had presented drama and opera at the Old Vic, ticketing them at affordable prices that were popular with laymen, and believed that works of art belonged to everybody. In that spirit, she began fundraising to rebuild Sadler’s Wells, joining forces with Ninette de Valois in 1928 to assemble the fifth iteration of the theatre, which opened Twelfth Night to crowds in an interior architected by the prolific Frank Matcham.

After four years of Vic-Wells drama productions, opera and ballet, Baylis decided to stop shuffling between the two venues and dedicated Sadler’s Wells to opera and ballet, with a new season in the autumn of 1935 that featured the stars of the future, and notably so for critics wooed by “the splendid dancing of the young newcomer Miss Margot Fonteyn, who has a compelling personality and exceptional gifts, though only just 16.”

Streamlining was a savvy move; though Britain’s first critically acclaimed opera ‘Peter Grimes’ later opened at Sadler’s Wells, in retrospect it was the first step to firmly establishing the venue as a specialist dance institution. Ninette De Valois was an Anglo-Irish dancer and director of classical ballet who went on to become known as the ‘godmother’ of ballet (and OM, CH and DBE by 1992). She founded the still renowned Royal Ballet company, and what eventually became the Birmingham Royal Ballet and the Royal Ballet School, from within Sadler’s Wells during World War II. The venue stood firm on its heels at this time and continued its programme of events, as well as acting as a refuge for the homeless.

By 1970, Rambert Dance and London Contemporary Dance had held residencies at Sadler’s Wells.

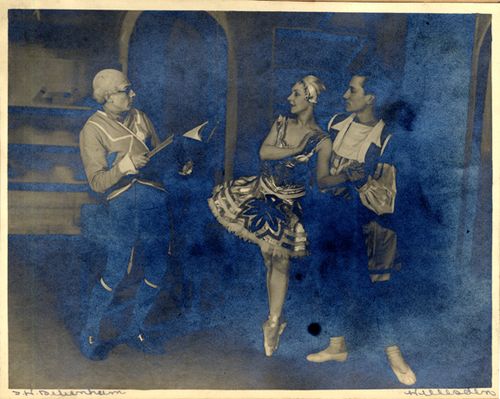

A ballet troupe in the mid-1900s, performing Coppelia at Sadler’s Wells – from the Islington Local History Centre

It was in 1994 that the new chief executive, Ian Albery, provided unhindered definition. With £54 million of funding, largely from the National Lottery, to hand, he transformed Sadler’s Wells into a purpose-built dance house. He had a time capsule buried under the centre stalls and called the bulldozers in, resurrecting the venue with a 15m2 sprung stage and 1500-capacity auditorium, a 200-seater for smaller works, and three rehearsal studios. Today, these host artists in residence and community based initiatives, such as City Academy’s Musical Theatre, Contemporary Dance, and Ballet classes – staying true to the mission of democratising the arts.

Sadler’s Wells now has a Grade II listing, as the redesign honours a history of drama both on and off the stage. It gives a nod to the past by preserving the skeleton of the Frank Matcham theatre (which itself retained bricks from the Victorian playhouse), and of course the historic wells. Under new directorship that began in 2004 and with a clear, contemporary artistic vision, Sadler’s Wells in the 21st century produces its own outstanding shows, receives touring performances from the UK and abroad, and hosts an annual festival of hip hop dance on a mission to continue to diversify within dance.

City Academy holds classes at 40 venues across London. Find out more about our locations and courses starting at Sadler’s Wells here >>>